The change in Armenia's political leadership in 2018 is presented by the incumbent regime as democracy’s victory, essentially, implying that the forced regime change was followed by two elections that were allegedly not rigged. Blocking the courts, laying the people on the asphalt by the Prime Minister's order and holding elections under the threat of a hammer are considered expressions of the people's free will. Therefore some questions arise that were discussed 2,500 years ago.

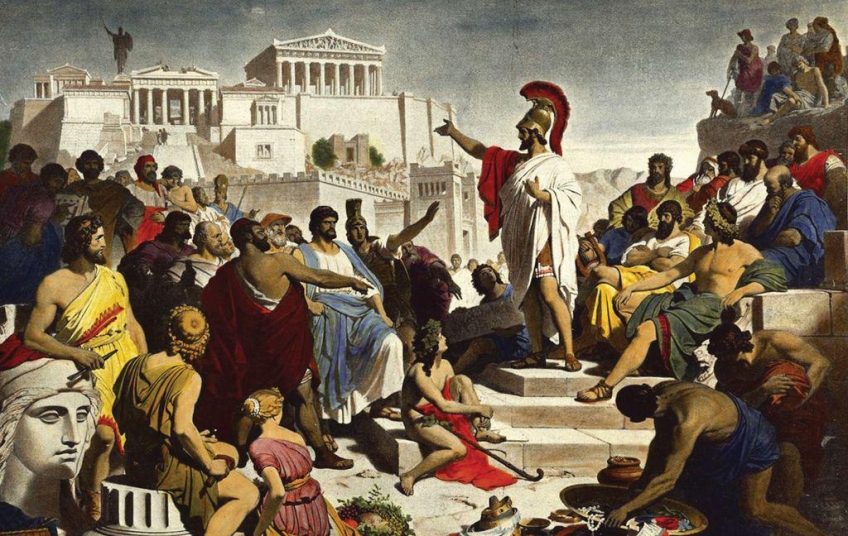

By far the most well-documented and studied example of democracy was originated in ancient Greek city-states, the largest of which did not exceed 10,000 inhabitants, and where it was not difficult to organize direct elections. Additionally, slaves, women, and metics (foreign residents in Athens) were not allowed to vote and did not participate in the city administration. However, Plato called democracy the power of “the envious poor” and warned that excessive democracy inevitably leads to dictatorship. In book VIII of his best–known work, The Republic (in Greek: Politeia (Πολιτεία), in Latin: De Republica) he claims that democracy generates tyranny.

This should be understood in the sense that the poor demanded confiscation of the property of the rich and equality of property, and since the majority of the voters were the poor, violence was needed to carry out such actions. At that time, populists and demagogues worked to satisfy the wishes of the masses in the hope of getting votes. Aristotle for his part, said that the true forms of government, therefore, were those in which the one, or the few, or the many, governed with a view to the common interest; but governments which rule with a view to the private interest, whether to the one, or the few or of the many, were perversions. Democracy was a kind of governance that had in view the interest of the needy only.

Starting from the 17th -18th centuries, when the churches were deprived of the monopoly of crowning the authorities, i.e. the legitimacy of the authorities was already determined not in the name of God, but through elections, fundamental problems ensued: can everyone participate in the elections and do they have enough knowledge and consciousness in order to vote in favor of the common good?

For example, in the 18th century, only 2-5 percent of the population had the right to vote in Great Britain and the United States. Women in England, Wales and Scotland received the vote on the same terms as men as a result of the Representation of the People Act 1928, and in the US the property qualification for voting was dropped only in the 1800s. Now everyone participates in the elections, but we are again faced with the same problems that Plato and Aristotle had talked about.

The most advanced country in that regard was the Soviet Union, which equalized the rights of women and men from 1918 and gave everyone the right to vote. However, that right was fictive, because they had to "vote" in favor of the only active political party and the only candidate registered in the polling station that was approved by the Communist Party.

As for Armenia, the populist leader came to power with his silent and voiceless supporters, who spoke only about what they were allowed to speak and only through the talking heads so instructed to speak. They "feed" the public with populist slogans and scare them with the threat of war. Accordingly, a rhetorical question arises whether democracy is always a fair and stable instrument for forming a government.

This is truly a rhetorical question, which in turn creates new questions because there is no other way to form a government. Will a political force or movement ever appear in Armenia that can speak to the people in a language comprehensible to them but not be populist and demagogic? We already have such a government, which brought the country to an unprecedented serious crisis and became the key issue of our modern political life.